In an era characterized by rapid technological advancement and evolving customer demands, financial institutions face new challenges to remain competitive. In response, they have been migrating their critical workloads to public clouds en masse. Public clouds offer tantalizing benefits—scalability, flexibility and operational resilience—yet the migration journey is neither swift nor straightforward. Due to the scale of these strategic transformations, considerable investment and extended timelines are required to execute them. As prominent financial institutions understand the nuances of the supplier landscape, they often lock in multiyear fixed-rate agreements, usually ranging from three to ten years, with cloud service partners (CSPs) to ensure operating cost stability and predictability.

With the world teetering on the brink of a major economic shift, a strategic conundrum has emerged.1 The prevailing costs of public cloud transformations may soon diverge starkly from initial projections. Moreover, the cessation of free money practices and evolving macroeconomic conditions now threaten the financial balance between these institutions and their CSPs.2 Higher commodity prices and interest rates, along with stagnant or burgeoning inflation, will continue to put operating cost pressures on CSPs. For early public cloud adopters, it is now conceivable that the cost for some CSPs to continue to provide services in some geographies may now surpass the revenue those services generate. Although this may be a short-term liability, a more pressing concern is what this could mean for both parties at the end of their long-term contract. As financial institutions transition from an extended period of rapid expansion and growth to a new era that focuses on delivering tangible and sustainable value, many IT professionals may face challenges, disruptions or uncertainties. This strategic shift in priorities will most likely require both mindset and technological adjustments.

Migrating to the Cloud

At the outset of public cloud adoption, it was common practice for financial institutions to apply relatively linear cost projections when formulating their business cases. Typically, the projected costs were simply derived by multiplying the current cost of major cloud computing services (e.g., storage, processing and tooling) against the institution’s anticipated future resourcing needs. However, once the public cloud services became openly available to staff across an organization, the rate of adoption and level of service consumption far exceeded the forecasted cost projections because operating costs were significantly higher than predicted. This elicited reactions from technology leadership teams in two ways. The first and most common reaction was to implement cloud resourcing caps, which in turn limited many of the forecasted benefits that the public cloud offers. The second reaction was that leadership teams started searching for additional cost savings in their resourcing or existing technology environments. This path typically led to measures such as reducing headcount, extending hardware life cycles, reducing maintenance or recycling old hardware (e.g., servers) for new purposes. As shown in figure 1, these processes led institutions to grapple to maintain control over their public cloud and legacy expenditures, resulting in their public cloud expenditures being higher and exhibiting more oscillatory patterns than their initial linear cost projections.

The potential for cost prediction errors may be further compounded in both small and large financial institutions due to the difficulties associated with accurately forecasting the true cost of concurrently maintaining two (legacy and public cloud), three (legacy, private and public cloud) or potentially more (legacy, private and multiple public clouds) hosting environments. Organizations were also often caught off guard by inaccuracies in their supplier cost projections and workforce composition needs, as the technical skills needed to build, maintain and operate these technology environments often require that staff be retrained, or supplementary resources be brought in to manage the environment.

Another potentially problematic area is security controls because the controls an institution requires for cloud-native environments can vary (e.g., hardware security modules or physical security of data centers), leading to cost duplications. As illustrated in figure 1, an institution is potentially going to observe limited or no cost reduction prior to entering the final phase (after T4) of their transformation. The institution will most likely encounter a significant increase in overall security and technology operating costs until this period due to operating multiple hosting environments simultaneously.

Higher commodity prices and interest rates, along with stagnant or burgeoning inflation, will continue to put operating cost pressures on CSPs.

At the outset of migration, these costs can be absorbed by institutions as they transition from capital expenditures (CapEx) to an operating expenditures (OpEx) model. CapEx models refer to purchasing and maintaining long-term assets (e.g., data centers or servers), whereas OpEx models reflect leased or on-demand services (e.g., processing and storage). When shifting from CapEx to OpEx, the duration of the shift is critical as the overall cost will increase during the transition period; this can create friction with the board and shareholders.

The Commonwealth Bank of Australia (CBA) provides a noteworthy case study for the challenges of migrating major financial institutions to the public cloud. CBA was an early adopter of the public cloud and had migrated workloads as early as 2010.3 However, in a recent market update, CBA’s CEO Matt Comyn told investors that the bank’s goal is now to have 95 percent of its technology operations on the public cloud by 2027.4 For perspective, CBA is approximately one-quarter of the size of JPMorgan Chase based on current market caps and customer volumes.5

Inside Major CSPs

While cloud services-related revenues at major CSPs continue to grow, so too do their operating costs. In 2022, Microsoft’s cloud revenue increased by 25 percent to US$15.2 billion, while its operating costs also increased by 20 percent. Microsoft noted that due to its planned infrastructure investments, it expected that operating costs would continue to rise, which might decrease its operating margins.6 Although increasing cloud operating income ratios is considered positive news for Microsoft, it comes at a cost to traditional Microsoft divisions that generate revenues from hardware and software sales.

At Amazon, net sales increased 9 percent to US$514 billion in FY22; however, operating income declined from US$24.9 billion in FY21 to US$12.2 billion in FY22. Operating losses surged to US$2.8 billion in FY22 (compared to the operating income of US$7.3 billion in FY21) in the North American segment. Likewise, the international segment’s operating loss increased from US$0.9 billion in FY21 to US$7.7 billion in FY22. Only the Amazon Web Services (AWS) segment experienced a year-over-year hike in operating income, from US$18.5 billion in FY21 to US$22.8 billion in FY22.7 The results indicate that Amazon’s margins are beginning to show weakness, despite significant gains in revenue growth, and unless this trend reverses in the near future, it may present a considerable challenge to Amazon’s future expansion strategies.

The situation at Alphabet (Google) is more challenging. Cloud revenues increased by 37 percent to US$7.1 billion in FY22 compared with FY21. Despite the significant revenue growth, its cloud services division still incurred a total operating loss of US$2.9 billion at the end of FY22.8 Even in the face of such losses, the results continue to demonstrate a sustained trend of declining deficits for Google Cloud Platform (GCP). Based on the current trajectory and projected tail revenues from existing GCP customers, it is anticipated the platform will become profitable within the next two years. In spite of this projection, Alphabet’s board is warning shareholders of significant ongoing costs related to building infrastructure and hiring and retaining top talent at the scale required to ensure it remains competitive within the CSP market. This uncertainty is reflected in Alphabet’s 10-K filing with the US Securities and Exchange Commission for FY21:

“Our investments in Google Services, Google Cloud, and Other Bets … ultimately may not be commercially viable or may not result in an adequate return of capital and, in pursuing new strategies, we may incur unanticipated liabilities. These endeavors may involve significant risks and uncertainties ... that may fail to adequately align incentives across the company or otherwise accomplish their objectives.”9

As cost pressures continue to mount in the extremely competitive CSP market, any major disruption event (e.g., a cyberattack) may be catastrophic not only for the service providers’ critical customers, such as financial institutions, but also for the long-term survivability of the CSPs.

As cost pressures continue to mount in the extremely competitive CSP market, any major disruption event (e.g., a cyberattack) may be catastrophic not only for the service providers’ critical customers, such as financial institutions but also for the long-term survivability of the CSPs. Any major incident can cause significant brand damage, which challenges the ability of a CSP to raise its service provider fees. In an era of intense competition and soaring inflation, this could require a CSP to incur sustained operating losses for an extended period, which may not be a viable business proposition in a time of higher interest rates.

The End of Introductory Rates

When financial institutions decide to move to the public cloud, there is always a concern about their practical exit options should their CSP fail to deliver services at the agreed levels or should the CSP decide to significantly increase their prices after the initial contract. Until recently, such concerns have been a theoretical exercise, as market forces have been keeping CSP prices suppressed. This has been driven by the declining cost of technology and because the three largest CSPs were prioritizing rapid growth over short-term value propositions. These factors provided an arbiter function that prevented any single CSP or multiple CSPs from increasing their prices. The fundamental difference between the prior decade and now is that all CSPs will need to increase their prices due to changing economic conditions and increasing operating costs.

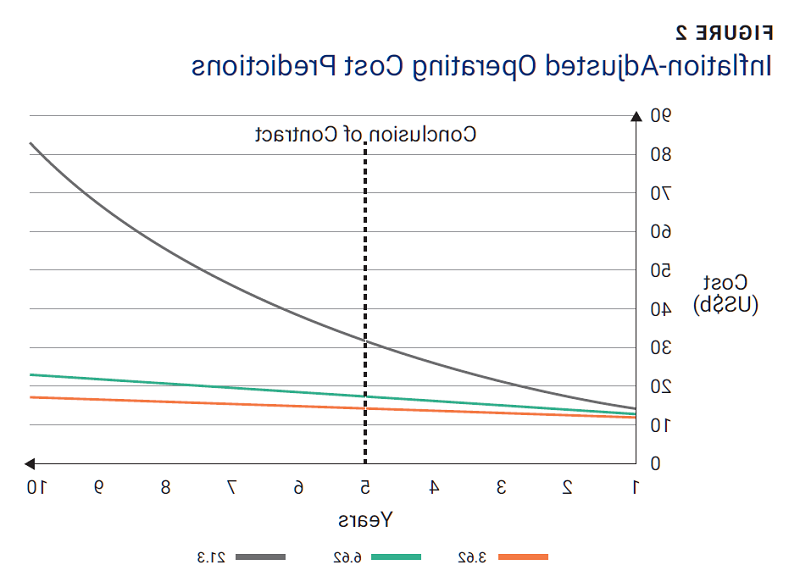

The ramifications of inflation on cloud services cost structures are shown in figure 2. In this scenario, A case study for JPMorgan Chase, a large financial institution with an annual technology expenditure of US$12 billion, is used.10 By juxtaposing this against the historical US average inflation rate of 3.62 percent, the prevailing rate of 6.6 percent11 and the mean FY22 CSPs operational cost surge of 21.3 percent, a more nuanced perspective about the evolving financial environment can be discerned.12

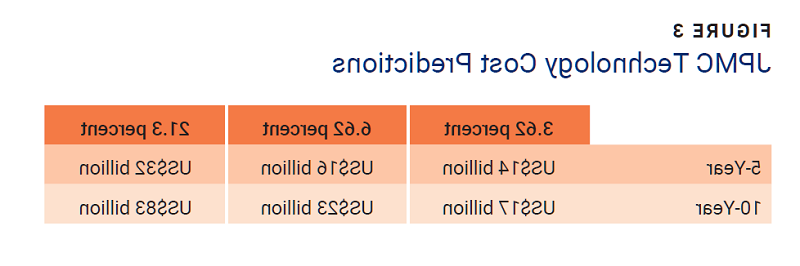

Although the difference between the historic average and the current rate of inflation depicted in figure 2 appears to be minimal when viewing the visual, the estimated operating cost differences over the five and 10-year periods are significant, as detailed in figure 3. Within the model, five years is used as the standardized contract duration, with the option for an extension of up to five additional years. It is worth noting that the operating costs to run on-premises hosting environments will also increase during this period. However, a fundamental difference that arises between CapEx and OpEx models is who owns the decision rights to implement cost-cutting measures such as extending hardware lifespans. As the CSP is contractually responsible for providing and maintaining infrastructure, this will not be an opt-in or opt-out decision—or a decision the financial institution is even consulted on. The decision to implement cost-saving measures is decided solely by the CSP.

These cost predictions also represent a direct challenge to multiple academic studies and professional practice material claims that the cost savings of moving to the public cloud are clear13 and that for some financial institutions, the savings could exceed 20 percent.14 Superficially, it may appear that US$2 billion per annum is not material for an institution the size of JPMorgan Chase, which is valued at more than US$350 billion, but every dollar matters. Banking is a highly competitive market sector, where the net interest margins on loans are spread between two and four percent. Accepting annual cost blowouts of two percent is unacceptable, let alone when the blowout relates to one of the institution’s largest ongoing operating costs.

Conclusion

While financial institutions rapidly adapt to the changing economic landscape, it may not be that simple for technology leaders. In many cases, they will have been the primary advocates to begin migrating to the public cloud, and any midflight pivot may now be perceived as an ill-conceived decision by the board or senior leadership. For many technology leaders, re-evaluating the business cases they used to justify their ongoing transitions to the cloud is a critical first step in responding to a dynamic operating environment. The decision to reverse course or to stay the course may prove to be one of the most challenging decisions for many technology leaders in their careers. There is no one solution to the problem, and each institution needs to carefully consider its options, as transitioning back to the CapEx model may not be feasible in the current economic conditions.

Endnotes

1 El-Erian, M.; “Not Just Another Recession: Why the Global Economy May Never Be the Same,” Foreign Affairs, 22 November 2022, http://www.foreignaffairs.com/world/not-just-another-recession-global-economy

2 Macquarie Group Limited, Investment Matters 2H22 Outlook, July 2022, Australia/New Zealand, http://www.macquarie.com.au/assets/bfs/documents/general/2H2022-Outlook-Final-WVOW.pdf

3 Howarth, B.; “Commonwealth Bank CIO Talks Cloud Computing,” CIO, 21 July 2010, http://www2.cio.com.au/article/353938/commonweath_bank_cio_talks_cloud_computing/

4 CommBank, “Making the Move to Public Cloud,” http://www.commbank.com.au/articles/careers/making-move-to-public-cloud.html

5 Financhill, “JPMorgan Chase vs. Commonwealth Bank of Australia Industry Stock Comparison,” October 2023, http://financhill.com/compare/industry/banks-diversified/jpm-vs-cbauf

6 Microsoft, Annual Report 2022, USA, 2022, http://www.microsoft.com/investor/reports/ar22/index.html

7 Amazon, “Amazon.com Announces Fourth Quarter Results,” 2 February 2023, http://ir.aboutamazon.com/news-release/news-release-details/2023/Amazon.com-Announces-Fourth-Quarter-Results/default.aspx

8 Alphabet Inc., 2022 Alphabet Annual Report, USA, 2022, http://abc.xyz/assets/d4/4f/a48b94d548d0b2fdc029a95e8c63/2022-alphabet-annual-report.pdf

9 US Securities and Exchange Commission, “Alphabet Inc. Form 10-K,” 2021, http://abc.xyz/assets/investor/static/pdf/20220202_alphabet_10K.pdf

10 JPMorgan Chase and Co., “This $12 Billion Tech Investment Could Disrupt Banking,” http://www.jpmorganchase.com/news-stories/tech-investment-could-disrupt-banking

11 US Inflation Calculator, “Historical Inflation Rates: 1914-2023,” 2023, http://www.usinflationcalculator.com/inflation/historical-inflation-rates/

12 Op cit Alphabet Inc.; Op cit Microsoft; Op cit Amazon

13 Rosati, P.; F. Fowley; C. Pahl; D. Taibi; T. Lynn; “Right Scaling for Right Pricing: A Case Study on Total Cost of Ownership Measurement for Cloud Migration,” 2019, http://arxiv.org/ftp/arxiv/papers/1908/1908.04136.pdf

14 Arora, C.; A. Bawcom; X. Lhuer; V. Sohoni; “Three Big Moves That Can Decide a Financial Institution’s Future in the Cloud,” McKinsey Digital, 3 August 2022, http://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/mckinsey-digital/our-insights/three-big-moves-that-can-decide-a-financial-institutions-future-in-the-cloud

Matthew Ryan, DCS, CISA, CISM, CGEIT, CRISC, CDPSE

Is an Australian cybersecurity researcher specializing in enterprise cybersecurity, strategy and risk management practices. He is the senior vice president of cyber and artificial intelligence (AI) risk for Macquarie Group Limited, where he oversees the investment bank’s cybersecurity and technology operations. Concurrently, he serves as a cybersecurity researcher for the University of New South Wales School of Systems and Computing (Canberra, Australia). He previously held specialist cybersecurity, resilience and management consulting roles with the Australian Prudential Regulatory Authority, Deloitte and the Australian Defence Forces.